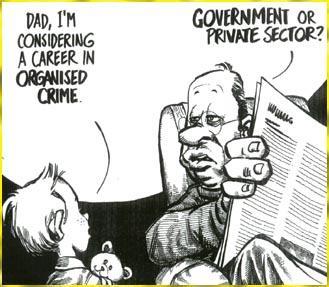

Carl Milsted on a meaningful distinction:

Liberty. Some love it because it provides wealth, opportunity, and other good things. Others declare that any denial of liberty is unacceptably evil, that liberty is a fundamental right of man. Both call themselves libertarians, and so they gather together at political conventions, seminars, and blog forums -- to call each other nasty names and do battle over the meaning of a word.

Read the rest, which is from the December issue of

Liberty, which has been advertising on the sidebar for a couple of weeks.

Milsted makes a distinction between what he calls "consequential" libertarians and "moralist" libertarians, a distinction that replicates itself everywhere in politics. Some people are just natural-born fanatics who turn to politics in a search for totalitarian

purity.

Fanatical demands for ideological purity in politics represent a totalitarian impulse, and are the bane of any really practical program for political action in a democratic system. To gain an effective governing majority requires the building of a coalition organized on fundamental principles and shared interests.

Zealous fanaticism can be useful in politics, boiling issues down to their stark fundamentals. I still remember the evening in 1995 when, having slipped the moorings of my Democratic upbringing, I sat down to dinner with a Republican Party official and the conversation turned to abortion. I mentioned my (small-L) libertarian opposition to taxpayer-funded abortion -- why should Catholics, for example, be taxed to pay for what is contrary to their expressed doctrine? -- and my host responded bluntly: "Abortion is murder and it ought to be against the law."

The Litmus-Test TrapThat statement has the virtue of simplicity, and has radical implications. Those who agree with it have a clear mandate for political involvement and it is thus scarcely surprising that pro-lifers remain the unbreakable backbone of the GOP today. Nothing makes me more furious than those "sophisticated" Republicans who sneer at pro-lifers. Without hard-core pro-lifers, there might never have been a Reagan presidency or a 1994 "Republican Revolution."

Yet the tendency toward fanaticism -- the radical certainty of the True Believer -- can have disastrous consequences in politics. There are many pro-lifers who make that issue a litmus test in such a way that it compels them to vote for bad politicians.

A perfect example of this problem is Nebraska Sen. Ben Nelson, the "pro-life" Democrat whose sellout cinched the Senate vote for ObamaCare. Many pro-lifers in Nebraska told themselves they could vote for Nelson because his partisan allegiance was negated by his declared pro-life principles.

Of course, many Republicans elected on the strength of their pro-life

bona fides have proved incompetent, corrupt or politically untrustworty, which creates the environment within which the election of pro-life Democrats becomes likely. And it is the single-issue litmus-test approach of the True Believers that is both cause and effect in such a scenario: They elect a bad Republican because he's "right" on their single issue and then, when he disappoints them, they replace him with a Democrat who is clever enough to position himself as pro-life. Whether this pattern ever actually results in the enactment of pro-life policies . . . well, that's an interesting question, isn't it?

'Anarchy Next Wednesday'Let us return, now, to Carl Milsted's attempt to deal with libertarian fanatics, in which he

describes a platform fight at the 2006 Libertarian Party convention:

At the time I was leading a major effort to reform the LP (the Libertarian Reform Caucus) to widen the LP's definition of "libertarian" so as to include a large fraction of voters who say they support both personal liberties and economic liberties, and to soften the party's platform away from its call for anarchy next Wednesday.

If you've ever attended a Libertarian Party gathering, you either smile at that description or become enraged by it. There are some Libertarians who oppose even the mildest concesion to pragmatism. They want an LP that is fanatically

pure and, as an inevitable result, politically impotent.

Purity is one of those ideas that have consequences and I made a reference to LP fanatics when

describing those consequences after the November 2008 election:

LGF -- which lately has been trying to purge Pam Geller as a Nazi (!) sympathizer -- doesn't mind saying "we blew it." And I agree: You blew it. And in fact, you still blow. Purge-happy partisan fanatics! Purge the Buchananites! Purge the libertarians! Purge the creationists! Purge the pro-lifers! Bobby Jindal is "political suicide!"

Purge, purge, purge, until the Republican Party is only you, and then maybe people will understand that this was your objective from the very beginning, you intolerant assholes. I am reminded of Bob Barr's description of the more fanatical Libertarian purists -- they don't want to belong to the Libertarian Party, they want to belong to the Libertarian Club.

Let these purging purists have their way, and you can plan to hold the 2012 Republican convention in Charles Johnson's living room. And I'll vote Libertarian again.

In the end, of course, CJ purged himself, but the fundamental point remains. It's this "club" mentality, the desire to act as membership chairmans of an exclusive sect composed entirely of one's fellow True Believers, that makes the fanatical quest for purity such a disastrous impulse in politics.

Big Boobs and Big TentsSuccessful politics requires a gregarious attitude, what we might call the Sheila Mosely Principle. In fall 1976, Sheila was a candidate for homecoming queen at Lithia Springs (Ga.) High School. Sheila was a popular cheerleader with an impressive C-cup rack, but there were other popular cheerleaders running for homecoming queen, one of whom was at least a D-cup.

So one day a couple weeks before homecoming, I was walking down the hall and encountered Sheila, who flashed a friendly smile and said, "Hi, Stacy." Maybe that wasn't the first time Sheila had ever spoken to me, but it was certainly the friendliest she'd ever been, and it made an impression.

Of course, I knew this unexpected gesture was

politically motivated, but it was nonethless impressive that Sheila had condescended to solicit the support of a stoner hoodlum like me. Impressive -- more impressive even than Kim Cantrell's D-cups -- and therefore Sheila got my vote.

Sheila understood that every vote counts. She wasn't going to let my stoner hoodlum status be an obstacle to her quest for homecoming queen. And that gregarious impulse, that willingness to solicit support from outside one's own social or political niche, was what made Ronald Reagan such an unequaled success in politics.

Reagan's "Big Tent" approach has been misunderstood and misapplied by many of his would-be successors, who have used it as an excuse for Clintonesque "triangulation," the politics of pre-emptive compromise. But Reagan was an unapologetic conservative, who did not feel the need to talk about being "kinder and gentler" or employ defensive modifiers like "compassionate."

From C-Cups to Tea Parties

Never renouncing his firm belief that liberalism was wrong --

a sound fundamental principle -- Reagan could nonetheless work with liberals and solicit their support for his agenda (rather than cooperating in a "kinder gentler" pursuit of the liberal agenda) because he had the same kind of winning self-confidence that permitted Sheila Moseley to smile and say "hi" to a hoodlum stoner.

The problem of fanatics who insist on purity is that their intolerance of dissent betrays a lack of confidence. If your ideas are so self-evidently true, what explains your totalitarian impulse to purge the impure?

Winners understand teamwork, and thus exhibit a cooperative, gregarious tendency in politics that rightly ought to be called populism. When I see intellectual idiots denouncing the Tea Party movement as "populist," I understand that they mean the term as a pejorative, a synonym for angry ignorance. But while Tea Party crowds are indeed angry about the current direction of policy in Washington, as individuals they are some of the most cheerful, friendly people you'd ever want to meet -- and certainly far less ignorant than their critics would have you believe.

Furthermore, the Tea Party people exhibit a very Reaganesque "Big Tent" attitude. Go to these rallies, and you'll find hard-core evangelical pro-lifers and libertarian bikers in happy coexistence, united by opposition to the big-government menace of Leviathan-on-the-Potomac. This is

what I've called "Libertarian Populism" and --

despite the dismissive snobbery of Julian Sanchez -- it is wrong to suppose that such hostility toward the elite is mere

ressentiment., when a two-decade bipartisan succession of Ivy-educated White House occupants (

Yale,

Yale Law,

Yale/Harvard MBA,

Columbia/Harvard Law) have led the nation to its current predicament.

If elitists can get over their fears of the populist mob, and if libertarians can get over their purist demand for "anarchy next Wednesday," there is a glimmer of hope for a real breakthrough. But we're not going to get there unless people start thinking like Sheila Mosely, whose friendly smile was enough to triumph even over a D-cup rack.

P.S.: Don't forget to visit Liberty magazine. If they're smart enough to advertise here, they must be

geniuses!

She's the ultimate celebrity Tweep, with more than 500,000 followers but, as of noon today, was only following 499 people, whereas I've got about 2,700 followers and am following nearly 1,300 people.

She's the ultimate celebrity Tweep, with more than 500,000 followers but, as of noon today, was only following 499 people, whereas I've got about 2,700 followers and am following nearly 1,300 people. In addition to Lombardi's maxim, there's also the inspiration of my role model, Pepe Le Pew:

In addition to Lombardi's maxim, there's also the inspiration of my role model, Pepe Le Pew: